Understanding ve(3,3)

Last week I brushed up on the Curve Wars and how bribes and the “vote escrow” mechanic were altering the liquidity sourcing and management dynamics in DeFi. As a natural progression of that story, today I’ll introduce another novel tokenomics model pioneered by one of the most prolific coders and founders in crypto, Andre Cronje.

The model I’m referring to is known as “ve(3,3).” If I could describe it in one phrase, it would be “vote escrow on steroids.” It combines the “vote escrow” primitive pioneered by Curve and the “3,3” staking/rebasing mechanic introduced by Olympus DAO.

Cronje is gearing up to launch a new decentralized exchange employing ve(3,3) tokenomics on Fantom. It’s an important event, because if the model works, it will change the liquidity sourcing and management game forever.

Unlike traditional finance, which tends to work in silos, DeFi is open and unburdened by patents, copyrights, or trademarks. In other words, stealing superior ideas in DeFi is permitted—even encouraged. Hence, if Cronje’s ve(3,3) model proves superior, many DeFi protocols will be forced to revamp their tokenomics and embrace it to remain competitive.

I’m not making the rules—it’s all game theory.

The premise of 3,3

Ever heard of the Prisoner’s Dilemma? It’s a classic case study from the field of game theory, which studies rational agents’ strategic interactions in situations where they make interdependent decisions. The interdependence forces each agent to consider the other agent’s possible decisions in formulating its strategy.

The simplest way to understand the implications of game theory is through the hypothetical scenario dubbed Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine that two criminal organization members, Alice and Bob, are arrested and put in solitary confinement without means of communicating with each other.

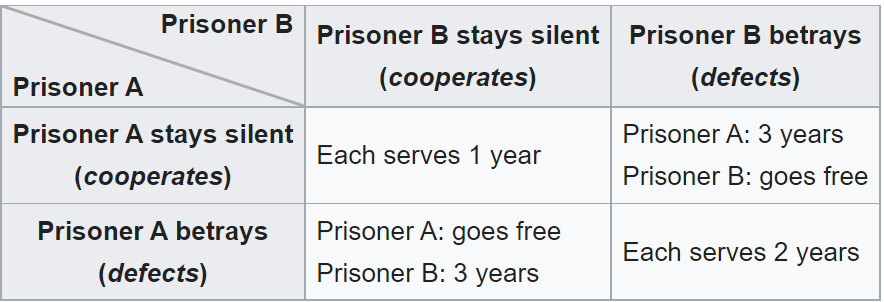

The police lack sufficient evidence to convict both on the principal charge but have enough to convict them on a smaller charge. So, they simultaneously offer each prisoner a bargain: either testify against your partner and go home, or stay silent, risk betrayal and go to prison. The possible outcomes are:

- If Alice and Bob both snitch, each serves two years in prison.

- If Alice snitches on Bob but Bob remains quiet, Alice is set free, and Bob serves three years.

- Vice versa, if Bob snitches on Alice but Alice remains silent, Alice gets three years, and Bob is set free.

- If Alice and Bob stay quiet, each serves only one year on the lesser charge.

As you can see from the above diagram, if both prisoners cooperate and stay silent, they’ll serve the least amount of time in prison. However, from an individual prisoner’s point of view, cooperating is a risky strategy because if the other prisoner snitches, they’ll do three years of prison time. Thus, snitching or defecting stands out as the best strategy for both players.

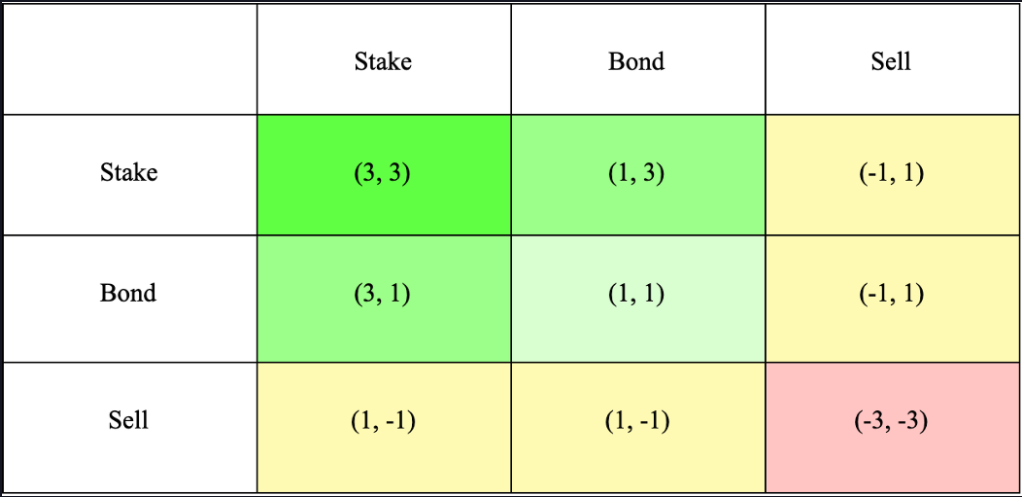

Now, back to crypto. OlympusDAO pioneered the 3,3 (cooperate, cooperate) tokenomics model by promoting reciprocity through making the implications of game theory explicit.

Unlike the prisoners in our hypothetical game, Olympus stakers can communicate, meaning they can theoretically reach consensus and keep cooperating (staking) because that is the most optimal action for everyone to take.

By staying staked (3,3), OHM holders are essentially cooperating to withhold the supply of OHM from the market, therefore raising OHM price and increasing market capitalization.

In a nutshell, the premise of 3,3 is: If we all cooperate or stake and none of us sell—we all get exponentially richer (at least on paper).

Upgrading to ve(3,3)

The “vote escrow” primitive pioneered and popularized by Curve is the mechanism of vote-locking tokens for a pre-set period in exchange for pro-rata voting rights, transaction fees, and additional token emissions. The longer the tokens are locked, the more voting power and higher rewards they give.

(I explained this mechanism in-depth in the previous issue of the radar, so make sure to read it if the next section is hard to follow.)

In Curve’s case, the CRV governance tokens are hard-capped. Projects stand to gain a significant competitive advantage by owning them, but can only acquire so many.

This creates a game-theoretical scenario where each project that uses Curve competes for the most amount of CRV, vote-lock it on the exchange for veCRV, leverage its voting power to direct new CRV emissions toward its pools, acquire more CRV and repeat the process all over.

One of the problems for veCRV holders in this model is that the new token emissions are slowly diluting them unless they’re the winning bidder to get them. Over time, this tends to concentrate power into the hands of the largest token holders like Convex protocol.

In improving upon and optimizing this model even further, Cronje put Curve’s vote escrow primitive on steroids by combining it with a clever iteration of OlympusDAO’s (3,3) mechanism.

With Cronje’s new ve(3,3)-based decentralized exchange called Solidly, liquidity providers will be able to either provide liquidity in exchange for transaction fees or stake their LP tokens in vote escrow for veLP tokens to earn from new tokens emissions.

The first brain fryer here is that, unlike Curve, which issues constant CRV emissions every week, Solidly emissions will be dynamic and adjusted as a percentage of the circulating token supply.

If 0% of the tokens are locked, emissions will be maxed out. If 50% of the tokens are locked, emissions will be 50% of the initial set distribution. If 100% of the tokens are locked, the weekly emissions will be zero.

The second brain fryer is the actual (3,3) part which introduces rebasing. Under the ve(3,3) model, vote escrow stakers or veLP token holders will grow their holdings proportional to the weekly emissions. This is how OHM stakers get such high APYs: more OHM is printed and distributed to them.

This means that vote escrow stakers won’t be diluted like on Curve. If the weekly token emissions increase the total token supply by 5%, vote escrow stakers will have their holdings increased by 5%. Hence, there’s more incentive to vote-lock tokens.

The main question is what is the most optimal strategy for each player—token holder or liquidity provider—in this game? Stake and hold LP tokens, provide liquidity without staking, simply hold the tokens, or maybe get in early, stake, withdraw initial investment as soon as possible and then let the profits roll until you can cash out a reasonably sized house?

We will see when Solidly launches. Game theory is, after all, a “theory.” Humans aren’t 100% predictable and Solidly will be the proving ground for the new model. At least we know what will be in the market’s spotlight in the coming weeks.

Did you like the content of this Email? Follow us on Twitter.

Our research team at SIMETRI is also constantly sharing alpha. So feel free to follow me: Stefan Stankovic, and my colleagues: Anton Tarasov, Sergey Yakovenko, and Nivesh Rustgi.